Care Delivery

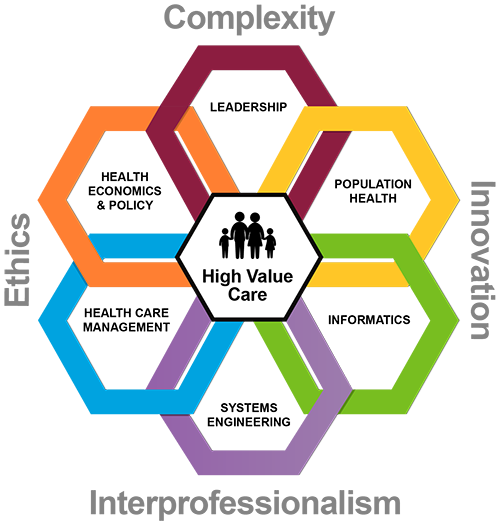

Health and personal care requires universally acknowledged methods to identify and address complex issues. This activity starts with collecting enough relevant information to allow us to draw pertinent conclusions about an individual’s strengths, deficits, risks, and problems; the meaning of signs and symptoms, distinguishing real problems from normal variations, identifying the need for additional analysis and intervention, distinguishing and relating the physical, functional, and psychosocial causes and consequences of illness and dysfunction, and identifying an individual’s values, goals, wishes, and prognosis. Taken together, this information enables pertinent, individualized care plans and interventions.

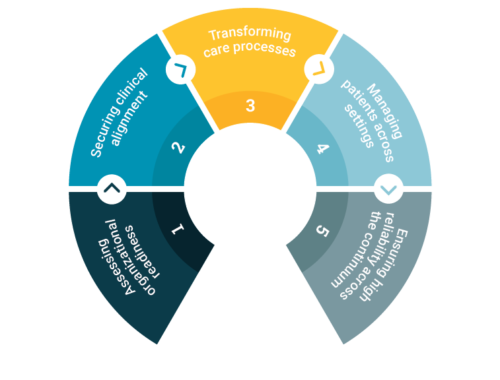

Steps in such a care delivery process, are: 1) Recognition/Assessment, 2) Cause Identification/Diagnosis, 3) Management/Treatment, and 4) Monitoring (Figure 1). The care delivery process is based upon thinking that is at the heart of modern medical, nursing, and pharmacy practice, and is consistent with standard problem solving and quality improvement approaches. While specific interventions may be controversial or may change with time, these principles and processes are enduring.

Advantages of a proper care delivery process?

A consistent, correct care delivery process facilitates care that meets all of the desirable quality attributes as identified by the Institute of Medicine: safe, effective, efficient, patient-centered, timely, and equitable.

Use of a systematic care delivery process reduces guess work and helps increase the likelihood that correct, safe care will be given, contributing to improved care quality, customer satisfaction, regulatory compliance, and financial performance, and reduced legal liability. For example, it is possible to target interventions for agitated behavior, pain, and anorexia/weight loss to maximize benefit and minimize risk. In contrast, interventions that skip key care process steps often become guesswork. Faithful adherence to the care delivery process enables rational medication use that maximizes effectiveness, minimizes risks and complications, and facilitates regulatory compliance. When all the diverse care providers and practitioners use this systematic approach to care for all residents, care delivery should become more consistent. A systematic care delivery process is also consistent with essential geriatrics and medical principles. Much of the care of long-term care residents and short-stay postacute patients–especially, those with complex conditions and multidimensional needs and problems–revolves around a handful of problems (falling, anorexia, increasing confusion, etc.). Many symptoms have diverse causes, and many conditions can cause multiple symptoms. Before care planning begins, it is critical to link diagnoses, problems, and treatments correctly. Symptoms or abnormalities should not be treated without trying to identify their causes. A proper care delivery process helps fill the critical gap between assessment and care planning. It provides a significant basis for process and outcome quality indicators. Understanding cause-and-effect relationships helps to target care and identify likely improvement, as a basis for evaluating the ultimate results.

Use of a systematic care delivery process reduces guess work and helps increase the likelihood that correct, safe care will be given, contributing to improved care quality, customer satisfaction, regulatory compliance, and financial performance, and reduced legal liability. For example, it is possible to target interventions for agitated behavior, pain, and anorexia/weight loss to maximize benefit and minimize risk. In contrast, interventions that skip key care process steps often become guesswork. Faithful adherence to the care delivery process enables rational medication use that maximizes effectiveness, minimizes risks and complications, and facilitates regulatory compliance. When all the diverse care providers and practitioners use this systematic approach to care for all residents, care delivery should become more consistent. A systematic care delivery process is also consistent with essential geriatrics and medical principles. Much of the care of long-term care residents and short-stay postacute patients–especially, those with complex conditions and multidimensional needs and problems–revolves around a handful of problems (falling, anorexia, increasing confusion, etc.). Many symptoms have diverse causes, and many conditions can cause multiple symptoms. Before care planning begins, it is critical to link diagnoses, problems, and treatments correctly. Symptoms or abnormalities should not be treated without trying to identify their causes. A proper care delivery process helps fill the critical gap between assessment and care planning. It provides a significant basis for process and outcome quality indicators. Understanding cause-and-effect relationships helps to target care and identify likely improvement, as a basis for evaluating the ultimate results.

Understanding the care delivery process permits identification of key functions and tasks associated with each phase; for example, formulate a detailed problem statement (Recognition) or recognize multiple coexisting causes of a symptom (Cause Identification). It is then possible to identify the skills and disciplines that are needed to perform those functions and tasks.

Critical Elements within Care Delivery

Care delivery process and its relation to survey process and regulations?

Nursing home regulations and related guidance do not substitute for good care. Capable staff, practitioners, and facility management recognize that they cannot rely on regulations as the primary guidance on how to care for sick, frail, chronically ill individuals. Survey instruments such as the Minimum Data Set (MDS) and Resident Assessment Protocols (RAPs) emphasize functional and psychosocial assessments and do not guide any discipline in the adequate assessment of physical problems or medical conditions, or how to identify the specific causes of problems in symptomatic individuals or how to select the right interventions from among options. Facilities should use the care delivery process to guide care that is compatible with regulatory requirements, not vice versa.

Ensuring an Effective Care Delivery

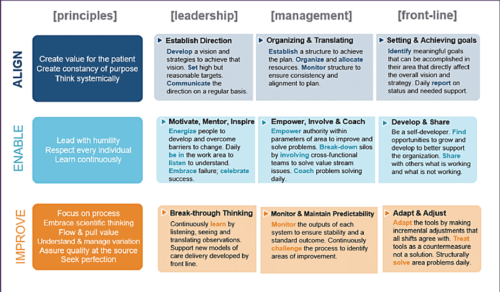

Compliance with the complete care delivery process is essential to providing long-term care that meets all of the attributes of quality. Promote the proper management focus. Capable administrators and management staff apply well-established quality-improvement and management principles to operate and oversee an effective care delivery system. Therefore, facility management should understand the key elements of the care delivery process (which does not mean they have to know how to diagnose and treat disease). Administrators must play a key role in ensuring that the care delivery process occurs correctly and consistently in their facilities.

Owners and administrators should understand what their management and staff are supposed to do, and how to identify when they do it right. They should provide clear job descriptions and job responsibilities; have systems for observing and matching performance with expectations; hold staff and practitioners accountable for their performance; provide regular and pertinent feedback; and use results to identify and correct root causes of practice and performance problems.

Promote the proper approach to regulatory compliance. Every nursing home must comply with regulatory requirements. While the OBRA regulations and related guidance provide broad expectations, they do not provide the primary route to regulatory compliance. The effort to address survey deficiencies must rely on understanding how to use the care delivery process and performance improvement principles to identify root causes of problems. Understanding the care delivery process reminds us that clinical problems often do not match up with a specific discipline. For example, a survey deficiency related to weight loss may ultimately relate to undetected adverse medication consequences or to the failure of nurses, consultant pharmacists, and physicians to recognize and address correctable causes of anorexia.

Promote the proper approach to regulatory compliance. Every nursing home must comply with regulatory requirements. While the OBRA regulations and related guidance provide broad expectations, they do not provide the primary route to regulatory compliance. The effort to address survey deficiencies must rely on understanding how to use the care delivery process and performance improvement principles to identify root causes of problems. Understanding the care delivery process reminds us that clinical problems often do not match up with a specific discipline. For example, a survey deficiency related to weight loss may ultimately relate to undetected adverse medication consequences or to the failure of nurses, consultant pharmacists, and physicians to recognize and address correctable causes of anorexia.

Promote the proper approach to risk management. Following the care delivery process means getting a complete "story" (onset, duration, location, intensity, etc.) about symptoms and looking at the whole patient picture before rushing to intervene. It means recognizing that it is improper to label individuals as "rehab" patient, IV patient, wound care patient, etc. It means recognizing that symptoms such as agitation, falling, anorexia, and increasing confusion often reflect the cumulative effects of multiple simultaneous conditions and factors. Valid risk reduction relies on understanding what is to be done and why before using medications and other high-risk interventions to try to "comply." Payment issues are always relevant, and may affect decisions at certain steps of the care process, but they should not result in skipping steps. The primary diagnosis or reason for admission often masks significant unidentified or unresolved comorbid conditions. Good practice requires recognizing and addressing significant modifiable risk factors before they are active or more advanced. Proper adherence to the care delivery process allows the staff and practitioners to anticipate problems better and allows them to explain to patients and families why the care may be more complicated, or the desired outcome more difficult to achieve, than expected. Sometimes, appropriately explaining the full picture will help the payer understand why they should authorize additional care or a longer stay.

The care delivery process is essential to adequate risk management. Ownership and key management (including the Administrator, Director of Nursing, and Medical Director) should support the consistent use of the care delivery process at all levels in the facility. This process is more likely to succeed with broad participation.

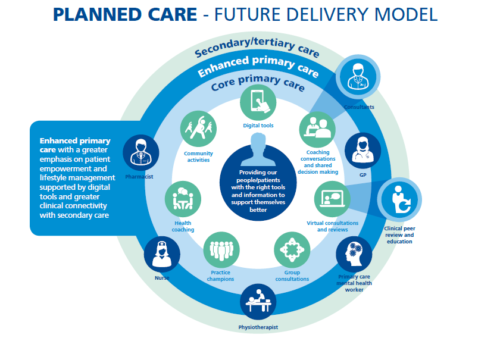

At a corporate level, most health plans are on record saying that the medical home model has promise for reducing cost and raising quality. Health plans may be preparing to support the medical home, but it seems that many will not be content to simply offer increased payment for recognized Patient Centered Medical Homes (PCMH) sites. Instead, many plans have ambitions to play a robust, ongoing role in the design and delivery of medical home services. This would help ensure that the health plan's contributions become a key part of the overall value proposition of any future medical home network or product. The provider-facing medical home formulas they are testing are surprisingly complex and often include both financial and operational components as abbreviated below:

- Financial support mechanisms usually combine three common building blocks: fee schedule enhancements, per-member-per-month payments for care management, and primary care pay-for-performance. (Total value across contracts varies wildly.)

- Operational support approaches range from hands-off to hands-on, with some plans going so far as to manage care teams or embed plan-employed care managers in practices. Some plans have also entered into information technology partnerships that invite or require providers to use payer-sponsored care management information services and tools as part of the medical home contract.

PCMH models are evolving toward rewarding primary care practices for reductions in total spending for patients continuum-wide. Under this approach, primary care physicians are incentivized for doing things that help reduce avoidable hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and inappropriate specialty care use.

Nationwide, health systems are taking a key steps to ensure immediate-term financial sustainability, including:

- Focusing on growth strategies ranging from increasing Primary Care Physician (PCP) panel size to entering narrow networks to backfill specialty and hospital volumes.

- Steering self-insured employees and families to PCMHs to capture cost reduction/quality improvement benefits

- Targeting Medicaid/uninsured populations for early rollout of PCMH services.

- Building joint-negotiating capacity through clinically integrated physician-hospital organizations (PHOs) and integrated health care delivery systems.

- Negotiating aligned incentives across the full continuum of care—for example, implementing performance incentives for avoiding preventable hospitalizations that offset decreased volume.

Five Future Trends that would impact Care Delivery

In a fee-for-service (FFS) model, health systems generate more revenue when patient volume increases. Under a value-based model, a person who shows up at an emergency room (ER) or a doctor's office becomes an expense rather than a source of revenue. In 2019, health systems and hospitals will likely move toward this value-based model at a faster pace than in previous years. But to succeed, they will need to work more closely with health plans. Here are five trends that I expect could impact health plans, health systems, and patients in 2019:

In a fee-for-service (FFS) model, health systems generate more revenue when patient volume increases. Under a value-based model, a person who shows up at an emergency room (ER) or a doctor's office becomes an expense rather than a source of revenue. In 2019, health systems and hospitals will likely move toward this value-based model at a faster pace than in previous years. But to succeed, they will need to work more closely with health plans. Here are five trends that I expect could impact health plans, health systems, and patients in 2019:

- Convergence and collaboration between health systems and health plans will become more important: As we move into 2019, the most successful health plans will likely be those that are able to connect consumers to their health care. Health plans are the only players in the health care ecosystem that have a complete dataset for each insured patient. This information will be important for health systems and physicians as they become more responsible for the long-term health of patients. Health care providers need health plans for their technology and their expertise in managing care, and health plans need providers because they understand care delivery and clinical effectiveness. Both sides should leverage each other's strengths to create a better and stronger health system in the US.

- Health systems will continue to focus more on the patient rather than the illness: The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) is more than three years old, but we are just beginning to see its impact on hospitals and health systems. We expect the law will affect health systems more profoundly in 2019, as more of them choose to take on shared and full-capitation risk contracts. There were a few early MACRA adopters in 2016 and 2017, and the trend accelerated in 2018 as health plans forged closer relationships with health systems to share risk. Many health systems are trying to figure out how to put their arms around the entire continuum of care. Historically, this has been more of the responsibility of health plans, which have always existed in a value-based world. In a value-based payment model, health systems and doctors should consider the full cradle-to-grave spectrum of care within a fixed premium payment. This could be another opportunity for health plans and providers to collaborate.

- Technology could help move patients to the center: Physicians spend 21 percent of their time on non-clinical paperwork. This takes away from the time they spend with patients—and can contribute to burnout. Artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and cognitive technologies could automate many of daily duties for physicians and clinicians and give them more time to practice medicine. Over the next three to five years, 100 percent of health care providers expect to make significant progress in adopting these technologies, according to our Human Capital Trends research. However, those respondents also acknowledged that they haven't made much progress yet. We believe that both enabling technologies (like EHRs) and emergent technologies (like blockchain, AI, etc.) will help improve the connectivity and engagement among health systems, health plans, and patients and families. Rather than requiring a patient to physically meet with a doctor, data from a patient's EHR could be used to help manage chronic illnesses without the patient having to meet with a clinician—another market signal that speaks to the increased focus on wellness for 2019.

- More patients could consider virtual health: Very few of us really enjoy going to the doctor, which causes some people to wait until a condition worsens before seeking care. This mentality drives up costs, including expenses related to ER visits. Virtual health could help patients communicate directly with caregivers. The technology can help physicians see more patients, deal with rising clinical complexity, and support patients as they take a greater role in their own care. However, just 14 percent of physicians have implemented technology that allows them to conduct virtual visits with patients, and only 17 percent use the technology for physician-to-physician consultations, according to the results from our 2018 Physician Survey on virtual care. This could be because implementation is often costly for providers, and many organizations are still weighing the return on investment, as well as existing fee-for-service reimbursement rules. Health system leaders should determine when physicians and other caregivers should be at the site of care delivery and when their work can be performed virtually. Last summer, the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) proposed that Medicare pay physicians for virtual check-ins and other tech-enabled services. Telehealth is also becoming a common feature in commercial health plans. As of 2016, 74 percent of large employer-sponsored health plans had incorporated telehealth into their benefits (up from 48 percent in 2015).

- There will be more focus on population health: Population health takes a broad look at the management of outcomes for all of a health system's patients. Specifically, population health includes efforts to use health care resources more effectively and efficiently to improve the lifetime health and well-being of a specific population. In addition to disease prevention, population health activities include promoting health and well-being. In recent years, there has been an increased focus on the social determinants of health, and the recognition by health care stakeholders that many of the factors that influence our health have less to do with health care and more to do with our environment, our stressors, our income and education, and our level of social interactions and sense of community. While health care organizations might be grappling with how to measure the ROI of these efforts, they can be critical as we shift to a focus on wellness. We expect to see the social determinants of health continue as a hot-button issue in the new year.

The truth is, we need to reduce injury and illness, and we need to manage chronic disease more effectively to reduce utilization and resource consumption. We should give people incentives to engage with the health system as early as possible to keep them healthier. That keeps costs down. We are still going to get sick, but we likely won't get as sick if we get patients (or members) into the system sooner and deal with health issues in real time before they become too acute.

The year 2000 is nearly two decades behind us, and the future of health is closer than we think. My colleague Doug Beaudoin recently sketched out a vision for health in the year 2040. He predicted that by then, health care stakeholders will be working cooperatively to improve the health of individuals and populations. I agree that we are headed in that direction, but to ensure we stay on the right trajectory, health plans, health systems, and patients should start to work more collaboratively with each other in 2019 and in subsequent years.

Care delivery process and its relation to survey process and regulations?

Care delivery process and its relation to survey process and regulations?

Leave a Reply