Increase in international food prices of today has triggered a new trend of cross-border land acquisitions by sovereign wealth funds, private equity funds, agricultural producers, and other key players in the food and agribusiness industry.—fueled by mistrust in international food markets, concern about political stability, and speculation on future demand for food.

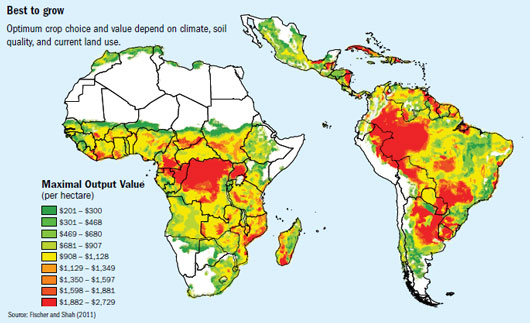

Throughout the world, it is estimated that 445 million hectares of land are uncultivated and available for farming, compared with about 1.5 billion hectares already under cultivation. About 201 million hectares are in sub-Saharan Africa, 123 million in Latin America, and 52 million in eastern Europe.

Agriculture is characterized by long periods between investment and production with low margins and is complicated by the vagaries of weather and microclimatic conditions. Small farmers all over the world have had to live with those challenges, but in many developing countries their ability to do so is hampered by low public spending on technology and infrastructure and by inadequate institutions.

Therefore, these transnational purchases are seen as an opportunity to overcome decades of under investment in developing countries’ agricultural sectors, to create jobs, and to bring new technology to the local agricultural sector. Others, though, denounce the transnational investments as a “land grab,” neglecting local rights, extracting short-term profits at the cost of long-term environmental sustainability, neglecting social standards, and fostering corruption on a large scale. In Madagascar the government fell in 2009 after news reports that it intended to transfer 1.3 million hectares to a South Korean company for free. Our research clarifies the factors underlying large transnational land acquisitions. This is a critical first step in the assessment of potential long-term effects of those investments and in identifying how governments can respond, through policy and regulation, to use land acquisitions in a way that promotes long-term economic development and reduces poverty.

Land Acquisition vs. Land Grabbing

Large-scale land acquisitions for agricultural purposes have become a pervasive topic in current debates on sustainable rural development. Focusing on issues such as food security, land governance, agricultural transitions, and access to resources, these debates involve a broad range of actors, including development practitioners, policymakers, investors, activists, and researchers – all of whom are striving to understand the rapidly unfolding phenomenon. While many, especially in the policy and practitioner world, welcome foreign direct investment in land as an urgently needed input into otherwise neglected agricultural development, others raise important questions about its potential social, economic, and environmental consequences.

Researchers seeking to further such debates with solid and timely evidence face considerable challenges. Data about transnational land deals are scarce and difficult to access, partly because of the high levels of secrecy around such deals. Moreover, the acquisition and development of arable land is a highly dynamic process.

CRITICAL FACTORS DETERMINING LAND ACQUISITION

Large or small farms?

The analysis of large-scale land deals relates to key development issues, including which agricultural production structure makes the most efficient use of existing resources and thus contributes to overall development. For instance, owner-operators usually are more motivated to adjust to microvariations in climate and seasonality because they better internalize the benefits resulting from their operations. Family-owned farms, rather than large companies run by hired labor, have thus been the most competitive all over the world, including in developed countries such as the United States. Such farms have contributed to poverty reduction in a wide range of settings. On the other hand, while some family farms can be quite large, investors usually aim to assemble tracts of land far larger than can be operated by a family. Is such a large-farm strategy viable in sub-Saharan Africa, where land is more abundant, as some have suggested.

The analysis of large-scale land deals relates to key development issues, including which agricultural production structure makes the most efficient use of existing resources and thus contributes to overall development. For instance, owner-operators usually are more motivated to adjust to microvariations in climate and seasonality because they better internalize the benefits resulting from their operations. Family-owned farms, rather than large companies run by hired labor, have thus been the most competitive all over the world, including in developed countries such as the United States. Such farms have contributed to poverty reduction in a wide range of settings. On the other hand, while some family farms can be quite large, investors usually aim to assemble tracts of land far larger than can be operated by a family. Is such a large-farm strategy viable in sub-Saharan Africa, where land is more abundant, as some have suggested.

There has been a perception that such large tracts of land were not necessarily efficient. But some of the recent emergence of large farms is rooted in technological developments in crop breeding, cultivation, and information technology that make labor supervision easier. These developments may indeed reduce the problems that have traditionally been associated with large agricultural operations and increase the benefits from vertical integration throughout the value chain from planting to food production.

But not all developments favor larger farms. Many technological innovations are not particularly scale biased. Information technology, for example, which can be used to better control a large farm, can also be used by small farmers to coordinate their efforts. Moreover, very large units of production often emerge because they can deal with market imperfections (access to finance), lack of public goods (infrastructure, education, or technology), and weak governance better than small ones. But, in a competitive and transparent environment where public goods are effectively provided, much smaller operational farm sizes could prevail. Indeed, anecdotal evidence suggests that, in many settings, farms are very large not because of inherent advantages of the technology but because of the superior ability of large operators to deal with market imperfections.

Ecological potential

The attractiveness of a country for new investment in large farming indeed depends on the availability and easy accessibility of uncultivated land with agricultural potential that can be developed without negative environmental consequences. So a measure is needed to gauge the potential agro-ecological suitability of land compared with its current use. Past attempts to measure the amount of land potentially available for agriculture suffered from conceptual and technical limitations. If potentially suitable land is either covered by forest or home to traditional communities, much of what could be available for agriculture may at the same time provide environmental and social benefits whose loss would significantly affect the economic desirability of an investment.

The attractiveness of a country for new investment in large farming indeed depends on the availability and easy accessibility of uncultivated land with agricultural potential that can be developed without negative environmental consequences. So a measure is needed to gauge the potential agro-ecological suitability of land compared with its current use. Past attempts to measure the amount of land potentially available for agriculture suffered from conceptual and technical limitations. If potentially suitable land is either covered by forest or home to traditional communities, much of what could be available for agriculture may at the same time provide environmental and social benefits whose loss would significantly affect the economic desirability of an investment.

To establish a benchmark for an area’s potential that takes these factors into account, we first divide the earth into some 2.5 million grid cells. We then use climatic and biophysical information (including soil quality) to compute maximum potential output of key agricultural commodities under given agro-ecological conditions (for example, without irrigation) for each grid cell (Fischer and Shah, 2011). Superimposing on this information layers of current land use and population density allows us to exclude areas already used for agriculture as well as forests, protected areas, and areas with a population threshold above a designated maximum. In this way, we derive a measure of countries’ potentially suitable agricultural area. Valuing this at world market prices allows us to determine the “optimum” crop choice as well as the net output value that can be obtained for that crop. The resulting output values, unadjusted for transportation costs, are illustrated in the map.

Why foreign investors want land

As expected, use of these measures together with a range of other measures to analyze determinants of bilateral land deals, suggests, not surprisingly, that a country’s attractiveness to investors correlates directly to large amounts of uncultivated land with the potential to generate significant output. A 10 percent increase, say, in potentially cultivable land in a host country would increase the number of projects in that country by about 5 percent, all other things equal.

But comparing potential yields with yields that are achieved on currently cultivated land also suggests that there is an immense possibility of increasing productivity on that land. In Africa, for example, none of the countries of interest to large investors achieves 25 percent of its potential yield, suggesting that enormous gains can be made by investments to increase productivity by smallholders on land they already farm, rather than by costly expansion into uncultivated lands. In line with this idea, our results suggest that countries with low yields and a potential to catch up are attractive targets for land acquisition. A strategy to attract investors to agriculture to fill these gaps and allow local farmers to thrive can yield large benefits—provided local community rights are respected and investors pay a fair price for the land. Translating potential into efficient farming activity, however, is not easy, partly because closing yield gaps in many cases requires government support—including in the area of technology, institutions, and infrastructure—in addition to efforts by private investors.

Land governance

There is indeed growing evidence that resource abundance can contribute to growth and poverty reduction only under the management of well-governed institutions. Otherwise, discoveries of oil, minerals, or diamonds often give rise to a “resource curse” characterized by widespread corruption and social polarization—or even violence—rather than broad-based development. Secure property rights, transparent processes to ensure ventures’ legitimacy, and a legal framework to enforce rights are generally considered a precondition for foreign direct investment. The large land areas required for agricultural production are more vulnerable to attack, pilferage, and sabotage and are more costly to fence off and police than, say, manufacturing plants, and the time it takes to start up production, especially for perennials such as oil palm, suggests that such ventures are particularly sensitive to a country’s investment climate.

There is indeed growing evidence that resource abundance can contribute to growth and poverty reduction only under the management of well-governed institutions. Otherwise, discoveries of oil, minerals, or diamonds often give rise to a “resource curse” characterized by widespread corruption and social polarization—or even violence—rather than broad-based development. Secure property rights, transparent processes to ensure ventures’ legitimacy, and a legal framework to enforce rights are generally considered a precondition for foreign direct investment. The large land areas required for agricultural production are more vulnerable to attack, pilferage, and sabotage and are more costly to fence off and police than, say, manufacturing plants, and the time it takes to start up production, especially for perennials such as oil palm, suggests that such ventures are particularly sensitive to a country’s investment climate.

Surprisingly, though, our econometric analysis provides evidence to the contrary. Countries with weak land sector governance are the ones most attractive to investors—at least as gauged by the number of land-related investments. A possible explanation is that it is easier to obtain land quickly and at low cost where the existing protection of land rights is weak, given that public protection may not matter to investors who can muster their own resources to defend their property rights. There is a danger, however, that the economic viability and long-term sustainability of investments can become compromised, and it may constitute a bad deal for host governments that transfer land well below its fair value.

Future Outlook and Trends

Renewed interest in large-scale land acquisition in developing countries represents an opportunity to overcome decades of under-investment in those countries’ agricultural sector, create employment, and foster technology transfer. At the same time the apparent attractiveness of host countries with weak land governance accentuates the associated risks and suggests that host countries’ policy and regulatory frameworks will be critical to the realization of this potential.

Concern about the potential negative effects of large-scale investment has given rise to draft legislation to limit land purchases by foreigners in a number of countries. If foreigners can use nationals as intermediaries, such measures do little to address the underlying issues and may exacerbate governance challenges by limiting competition. A more appropriate policy response would place priority on efforts to improve land governance—by recognizing local rights and educating local populations about the value of their land, their legal rights, and ways to exercise those rights. The terms of land transfers must be well known and understood and must conform to basic social and environmental safeguards; and compliance with them must be monitored. Many countries have declared a moratorium on land purchases by outsiders until such safeguards are in place. Also, given the size of the phenomenon and the dangers it can pose, a global effort is needed to document cross-national investments in coordination with domestic authorities.

Research on large-scale land acquisition in the past five years has been confronted with substantial challenges. It has had to respond to a fast-moving context, and at the same time has been expected to provide urgently needed evidence for policy and operate in real time. In-depth case studies seeking to understand the complex processes in concrete geographical contexts have been accused of being too slow and of limited validity when it comes to scaling up or scaling out findings, while endeavours to aggregate hectares and describe the overall scale of land deals have been struggling with data quality, triangulation methods, unclear definitions, and rapidly changing figures. In light of these criticisms, and encouraged by the attention and commitment that the debate has received from many different actors, some authors have called for a new phase of research: one that should be devoted to reflection, analysis, and to gaining deeper understandings of investments in land.

Different scenarios point to large differences in future land-use

This scenario demonstrates, that in many regions, significant changes in land-use, demand, and condition can be expected in the coming decades, mainly as a result of the combination of increased population and wealth, leading to an increasing demand for food, shifts towards more meat and land-intensive foods, increased demand for fiber and energy, urbanization, accelerating climate change, and continued local declines in land cover, productivity, and soil organic carbon.

This scenario demonstrates, that in many regions, significant changes in land-use, demand, and condition can be expected in the coming decades, mainly as a result of the combination of increased population and wealth, leading to an increasing demand for food, shifts towards more meat and land-intensive foods, increased demand for fiber and energy, urbanization, accelerating climate change, and continued local declines in land cover, productivity, and soil organic carbon.

These drivers will influence high and low river discharges, water scarcity, aridity, crop yields, agricultural land expansion, land as carbon source and sink, and biodiversity. Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and North Africa, South Asia and, to a lesser extent, Southeast Asia face an alarming combination of environmental and socio-economic challenges that will increase the pressures on land-based goods and services in the future. As a consequence, the multi-dimensional impacts on human security may lead to unmanageable problems and risks.

Response pathways need to help alleviate land pressures and achieve a more equitable balance between environmental and socio-economic trade-offs. It is the sum total of our individual decisions – as heads of households, consumers, producers, business owners, and policymakers – that is leading to a global failure in achieving food, water, and energy security for all while mitigating climate change and halting biodiversity loss. Like our response to climate change, a business-as-usual approach is insufficient to address the magnitude of this challenge. Such responses need to address population growth, consumption levels, diets, yield gaps for all commodities, the efficient use of space, water, materials, and energy, deforestation, food waste and post-harvest losses, climate change, and the conversion of natural areas. Land governance at the local, national and international scale coupled with enlightened land use planning and land management systems will be essential to navigate such a transition.

FOOD SECURITY AND AGRICULTURE

Agriculture and livestock cover over one-third of the world’s land surface, dwarfing all other land uses. Intensification, driven by a lucrative but largely inefficient food system, has boosted production. However, it has also disturbed cultural landscapes, sustained over thousands of years, and accelerated land and soil degradation, water shortages, and pollution. Agricultural expansion is hastening the loss of species and natural habitats. In spite of production increases, we are now experiencing widespread food insecurity in what should be a world of plenty.

Agriculture and livestock cover over one-third of the world’s land surface, dwarfing all other land uses. Intensification, driven by a lucrative but largely inefficient food system, has boosted production. However, it has also disturbed cultural landscapes, sustained over thousands of years, and accelerated land and soil degradation, water shortages, and pollution. Agricultural expansion is hastening the loss of species and natural habitats. In spite of production increases, we are now experiencing widespread food insecurity in what should be a world of plenty.

Proven and cost-effective alternatives to minimize these impacts already exist. Overall, agriculture needs to be more effectively integrated with other land use sectors. Multifunctional approaches to food production are needed, recognizing that land provides many other vital services. Key elements include increasing productivity and nutritional values from a given area of land, reducing offsite or downstream impacts on the environment, and promoting more local production, less land-intensive diets, and a reduction in food waste.

WATER RESOURCES

Rising water demand creates shortages, depletes groundwater sources, and results in high salt levels in soils. At the same time, wetlands are rapidly disappearing due to drainage, conversion, and the disruption of natural flows. These trends have serious health and environmental impacts: reducing ecosystem services and biodiversity, and resulting in high carbon emissions, soil subsidence, loss of productive land, and water insecurity. The current business model for agriculture, energy, and industry, including water pricing and trading, creates perverse incentives to waste water. Rapid unplanned urbanization and climate change make things worse.

Rising water demand creates shortages, depletes groundwater sources, and results in high salt levels in soils. At the same time, wetlands are rapidly disappearing due to drainage, conversion, and the disruption of natural flows. These trends have serious health and environmental impacts: reducing ecosystem services and biodiversity, and resulting in high carbon emissions, soil subsidence, loss of productive land, and water insecurity. The current business model for agriculture, energy, and industry, including water pricing and trading, creates perverse incentives to waste water. Rapid unplanned urbanization and climate change make things worse.

An integrated approach to land and water resource management is essential: this entails reducing demand and increasing use efficiency, protecting and restoring wetlands and watersheds in our working landscapes, providing incentives for sustainable use, and designing more sustainable cities. We have the technical know‑how to sustainably manage global water supplies, but we need coordinated action and the political will to incentivize equitable water sharing and improve management practices at progressively larger scales.

Water security is being undermined, in particular by the combination of unsuitable agricultural models, rapid demographic changes, and the destabilizing effects of climate change. Poor choices from the individual to the national level exacerbate the situation. Countries and communities are suffering from both shortages and excesses. The loss of wetlands, declines in water quality, and dramatic changes to the flow regimes of major hydrological systems are leading to a collapse in freshwater biodiversity and essential ecosystem services.

Improving water security requires an integrated, cross-sectoral approach which capitalizes on the links between the land management practices and the health of hydrological systems. In sum, some of the most critical steps include: more efficient water use in agriculture, industry, energy, and households; regulation and legislation, including pricing and allocation, to encourage efficiency; and increased protection and restoration to improve overall ecosystem functioning in the watershed. The technical know-how to help solve the water crisis is largely known; the next step is to apply these lessons learned at the scale required.

BIODIVERSITY AND SOIL

As population and consumption levels rise, natural ecosystems are being replaced by agriculture, energy, mining, and settlement. Poor land management leads to widespread loss of soil biodiversity, undermining food production systems throughout the world. Ecosystems are collapsing under the onslaught of deforestation, grassland loss, wetland drainage, and flow disruptions, all leading to a biodiversity crisis and the fastest extinction rate in the Earth’s history.

As population and consumption levels rise, natural ecosystems are being replaced by agriculture, energy, mining, and settlement. Poor land management leads to widespread loss of soil biodiversity, undermining food production systems throughout the world. Ecosystems are collapsing under the onslaught of deforestation, grassland loss, wetland drainage, and flow disruptions, all leading to a biodiversity crisis and the fastest extinction rate in the Earth’s history.

Yet we depend on living soil and the biodiversity that underpins functioning ecosystems and supports productive land-based natural capital. Threats are increasing which require a committed and sustained response. A mixture of protection, sustainable management and, where necessary, restoration is needed at a landscape scale to ensure the future of a diverse, living planet.

These three elements – conservation, sustainable management, and restoration – are integral parts of a single coherent management framework, commonly known as the landscape approach defined as: A conceptual framework whereby stakeholders in a landscape aim to reconcile competing social, economic and environmental objectives.

In order to operate on a relatively large scale, with what will inevitably be a broad range of competing interests, at its core the landscape approach entails negotiating trade-offs between different stakeholders. Ensuring that biodiversity conservation and the protection of a suite of ecosystem services endure against narrower and more personal interests requires long-term commitment, strong and locally embedded leadership, clear policies and guidance, and the provision of adequate finance from grants, public money, and private investments.

ENERGY AND CLIMATE

Abundant energy drives the world economy. But it comes at a price: our efforts to extract energy from fossil fuels and renewable sources take up large amounts of land. The pollution generated by energy production and consumption, including the burning of biomass, is altering the ecology of the entire planet.

Abundant energy drives the world economy. But it comes at a price: our efforts to extract energy from fossil fuels and renewable sources take up large amounts of land. The pollution generated by energy production and consumption, including the burning of biomass, is altering the ecology of the entire planet.

Climate change is the largest and most serious of these impacts, created mainly by fossil fuel burning together with significant greenhouse gas emissions from forest loss and the food system. While land is both a source and victim of climate change, it is also a part of the solution. Sustainable land management practices can contribute to climate mitigation strategies by halting and reversing the loss of greenhouse gases from land-based sources and can provide irreplaceable ecosystem services that help society to adapt to the impacts of climate change.

Responses to these challenges sound simple: less polluting energy sources, more efficient, energysaving solutions, and land use and management practices that prioritize the conservation of carbon in the soil. However, agreeing on what this means in practice has proved challenging, and implementing equitable clean energy strategies and scaling up sustainable land management more challenging still.

Reconciling rapidly increasing food demand with the pressing need to address global climate change by stabilizing or reducing emissions from agriculture is a complex problem requiring novel policy measures that incentivize best practices. Climate mitigation policies shouldtherefore be directed to locations where crops have both high emissions and high intensities. Findings clearly indicate that climate mitigation policies for croplands should prioritize elimination of peatland draining. Dietary shifts also have a high potential to help reduce carbon losses.

Some believe that nuclear power, whatever its hazards, is preferable to our continued reliance on fossil fuels, while others argue for a non-nuclear, renewable energy future. Some analysts believe that oil supply has peaked and that the world faces real energy shortages94 while others disagree. The extent to which countries should rely on hydropower remains a subject of deep controversy. The momentum to continue with business-as-usual approaches is enormous, and major industry players have the power to create energy futures that profit their own industries. Strategies that address the twin challenges of energy and climate are starting to emerge, but are generally doing so piecemeal and much more slowly than we need.

URBANIZATION

The millennia-old relationship between town and country is being transformed. Rapid urbanization is taking place all over the world, driven largely by rural migration, resulting in urban sprawl and slum developments as well as in the development of high quality infrastructure and overall improvement in the standard of living. If current projections are accurate, 66 per cent of the world’s population will be living in cities by 2050. This is having dramatic impacts on the environment and increasing pressure on limited land resources; future urban expansion is likely to result in the loss of some of our more productive croplands.

The millennia-old relationship between town and country is being transformed. Rapid urbanization is taking place all over the world, driven largely by rural migration, resulting in urban sprawl and slum developments as well as in the development of high quality infrastructure and overall improvement in the standard of living. If current projections are accurate, 66 per cent of the world’s population will be living in cities by 2050. This is having dramatic impacts on the environment and increasing pressure on limited land resources; future urban expansion is likely to result in the loss of some of our more productive croplands.

The footprint of cities extends far beyond their boundaries due to the demand for food and water as well as transport and energy infrastructure. But cities can offer economies of scale with respect to resource use and environmental impacts. The concept of sustainable cities is gaining ground but urban planners are struggling to put these approaches into practice.

Cities are and will likely continue to be drivers of economic growth, requiring large public investments. They will also continue to have impacts on land resources and associated ecosystem services that make up the natural infrastructure on which they depend. It is projected that 65 per cent of all urban land area in 2030 will have been urbanized in the first three decades of the 21st century. Urban development decisions are long-term and hard to reverse. Policies to ensure sustainable urbanization are urgently needed given the current trends.

The growth in the importance and extent of cities is transforming our approach to governance. As economic activities become more dispersed as a result of privatization, deregulation, and increasing globalization, new strategic alliances among cities are being formed as a green alternative to traditional national territories. Greater collaboration between cities in sharing best practices will be vital for developing sustainability. Some cities are already engaging in cooperative partnerships and beginning to take a more active role in resource management and impacts on the regional or even global scale.

For example, city responses to GHG emissions include the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group and the World Mayor’s Council on Climate Change.

DRYLANDS

Drylands cover 41 per cent of the land surface, produce 44 per cent of the crops, and contain over 2 billion people and half of the world’s livestock. Drylands are often regions of water scarcity yet with immensely rich biodiversity, including some of the most iconic species. They are also home to a diverse human culture including some of the world’s largest cities.

Drylands cover 41 per cent of the land surface, produce 44 per cent of the crops, and contain over 2 billion people and half of the world’s livestock. Drylands are often regions of water scarcity yet with immensely rich biodiversity, including some of the most iconic species. They are also home to a diverse human culture including some of the world’s largest cities.

Rural communities in drylands are often poorer than elsewhere and the land is more vulnerable to degradation from climate change and direct human pressures. Poor management can lead to desertification. We know how to manage drylands sustainably, but often do not achieve this in practice; policies and agricultural systems need to be transformed if we are to avoid the continued loss of health and productivity in the drylands.

A strategic agenda for managing drylands sustainably should revolve around the three established pillars of sustainability: social, environmental, and economic.

- Environmental sustainability in drylands requires a major overhaul of the natural resource sector, integrating agriculture and environmental management, increasing awareness of dryland issues, and not treating food production as an extractive industry. Soil is produced slowly in arid conditions and often regarded as a finite, nonrenewable resource; in the future, agriculture must ultimately put back into the soil as much as it takes out. It is particularly important to broaden our understanding of biodiversity, above and below ground, and to develop agriculture practices around the recognition that organic carbon, the prime indicator of soil fertility, is itself a part of biodiversity. Farmers, as stewards of soil carbon, are at the heart of the effort to address the biggest environmental challenges of our time: biodiversity loss, climate change, and land degradation.

- Social sustainability and stability in the drylands must be strengthened through the development of human capital, including improved access to basic services like education, health, and security. It should also include secure land tenure, improved social protection, and better management of and planning for the profound social pressures currently underway, such as urbanization, rural poverty, and the continued marginalization of women. Social sustainability requires effective institutions for the proper governance of natural and economic resources, and will only be achieved when human rights are respected as the foundation for peopleoriented development.

- Economic sustainability must build upon, and ultimately contribute to, ecological and social sustainability. It requires investment in value chains that reflect the essential diversity of dryland production systems, including capitalizing on environmental services and the certification of sustainably produced goods. This includes supporting the development of small- and mediumsized enterprises that increase added value locally and create jobs for the growing urban poor. It also requires an effort to overcome transaction costs, particularly those associated with access to information and technology transfers. For this, enabling investments from the public sector are needed in order to unlock private sector engagement and to overturn the legacy of underinvestment. Economic sustainability in the drylands must be built around sound risk-management, including the efficient management of soil and water, and the strengthening of locally-proven land management practices.

Leave a Reply